The relationship of Christianity and violence is the subject of controversy because some of its core teachings advocate peace, love and compassion while other teachings have been used to justify the use of violence.[1][2][3] Peace, compassion and forgiveness of wrongs done by others are key elements of Christian teaching. However, Christians have struggled since the days of the Church Fathers with the question of when the use of force is justified. Such debates have led to concepts such as just war theory. Throughout history, certain teachings from the Old Testament, the New Testament and Christian theology have been used to justify the use of force against heretics, sinners and external enemies.

In Letter to a Christian Nation, critic of religion Sam Harris writes that "...faith inspires violence in at least two ways. First, people often kill other human beings because they believe that the creator of the universe wants them to do it... Second, far greater numbers of people fall into conflict with one another because they define their moral community on the basis of their religious affiliation..."[4] However, Professor David Bentley Hart argues that while "Some kill because their faith commands them to" others "kill because they have no faith and hence believe all things are permitted to them. Polytheists, monotheists, and atheists kill - indeed, this last class is especially prolifically homicidal, if the evidence of the twentieth century is to be consulted.".[5]

Christian theologians point to a strong doctrinal and historical imperative within Christianity against violence, particularly Jesus' Sermon on the Mount, which taught nonviolence and "love of enemies". For example, Weaver asserts that Jesus' pacifism was "preserved in the justifiable war doctrine that declares all war as sin even when declaring it occasionally a necessary evil, and in the prohibition of fighting by monastics and clergy as well as in a persistent tradition of Christian pacifism."[6]

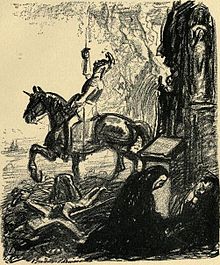

The Crusades were a series of military campaigns fought mainly between European Christians andMuslims. Shown here is a battle scene from the First Crusade

The Crusades were a series of military campaigns fought mainly between European Christians andMuslims. Shown here is a battle scene from the First CrusadeDefinition of violence

Abhijit Nayak writes that:

The word "violence" can be defined to extend far beyond pain and shedding blood. It carries the meaning of physical force, violent language, fury and, more importantly, forcible interference.[7]

Terence Fretheim writes:

For many people, ... only physical violence truly qualifies as violence. But, certainly, violence is more than killing people, unless one includes all those words and actions that kill people slowly. The effect of limitation to a “killing fields” perspective is the widespread neglect of many other forms of violence. We must insist that violence also refers to that which is psychologically destructive, that which demeans, damages, or depersonalizes others. In view of these considerations, violence may be defined as follows: any action, verbal or nonverbal, oral or written, physical or psychical, active or passive, public or private, individual or institutional/societal, human or divine, in whatever degree of intensity, that abuses, violates, injures, or kills. Some of the most pervasive and most dangerous forms of violence are those that are often hidden from view (against women and children, especially); just beneath the surface in many of our homes, churches, and communities is abuse enough to freeze the blood. Moreover, many forms of systemic violence often slip past our attention because they are so much a part of the infrastructure of life (e.g., racism, sexism, ageism).[8]

Heitman and Hagan identify the Inquisition, Crusades, Wars of Religion and antisemitism as being "among the most notorious examples of Christian violence".[9] To this list, J. Denny Weaver adds, "warrior popes, support for capital punishment, corporal punishment under the guise of 'spare the rod and spoil the child,' justifications of slavery, world-wide colonialism in the name of conversion to Christianity, the systemic violence of women subjected to men." Weaver employs a broader definition of violence that extends the meaning of the word to cover "harm or damage", not just physical violence per se. Thus, under his definition, Christian violence includes "forms of systemic violence such as poverty, racism, and sexism."[6]

Christianity's relationship with violence

| This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. Such statements should be clarified or removed. (February 2011) |

Further information: Religious violence

Charles Selengut characterizes the phrase "religion and violence" as "jarring", asserting that "religion is thought to be opposed to violence and a force for peace and reconciliation. He acknowledges, however, that "the history and scriptures of the world's religions tell stories of violence and war as they speak of peace and love."[10]

[edit]Religion and violence

Main article: Religion and violence

Critics claim that all religions harm society:[11][page needed][12][page needed]

- Religions sometimes use war, violence, and terrorism to promote their religious goals

- Religious leaders contribute to secular wars and terrorism by endorsing or supporting the violence

- Religious fervor is exploited by secular leaders to support war and terrorism

- Promotes exclusivism that inevitably fosters violence against those that are considered outsiders.[13]

- Recent secularism frees religious members from having to make practical, moral choices. Limiting violence may no longer be an essential principal, since religion is no longer in charge.[14]

[edit]Claims that Christianity has a "violent side"

Many authors highlight the ironical contradiction between Christianity's claims to be centered on "love and peace" while, at the same time, harboring a "violent side". For example, Mark Juergensmeyer argues: "that despite its central tenets of love and peace, Christianity—like most traditions—has always had a violent side. The bloody history of the tradition has provided images as disturbing as those provided by Islam orSikhism, and violent conflict is vividly portrayed in the Bible. This history and these biblical images have provided the raw material for theologically justifying the violence of contemporary Christian groups. For example, attacks on abortion clinics have been viewed not only as assaults on a practice that Christians regard as immoral, but also as skirmishes in a grand confrontation between forces of evil and good that has social and political implications."[15]:19-20, sometimes referred to as Spiritual warfare. The statement attributed to Jesus "I come not to bring peace, but to bring a sword" has been interpreted by some as a call to arms to Christians.[15]

In response, Christian apologists such as Miroslav Volf and J. Denny Weaver reject charges that Christianity is a violent religion, arguing that certain aspects of Christianity might be misused to support violence but that a genuine interpretation of its core elements would not sanction human violence but would instead resist it. Among the examples that are commonly used to argue that Christianity is a violent religion, J. Denny Weaver lists "(the) crusades, the multiple blessings of wars, warrior popes, support for capital punishment, corporal punishment under the guise of 'spare the rod and spoil the child,' justifications of slavery, world-wide colonialism in the name of conversion to Christianity, the systemic violence of women subjected to men". Weaver characterizes the counter-argument as focusing on "Jesus, the beginning point of Christian faith,... whose Sermon on the Mount taught nonviolence and love of enemies,; who faced his accusers nonviolent death;whose nonviolent teaching inspired the first centuries of pacifist Christian history and was subsequently preserved in the justifiable war doctrine that declares all war as sin even when declaring it occasionally a necessary evil, and in the prohibition of fighting by monastics and clergy as well as in a persistent tradition of Christian pacifism."[6]

Miroslav Volf acknowledges that "many contemporaries see religion as a pernicious social ill that needs aggressive treatment rather than a medicine from which cure is expected." However, Volf contests this claim that "(the) Christian faith, as one of the major world religions, predominantly fosters violence." Instead of this negative assessment, Volf argues that Christianity "should be seen as a contributor to more peaceful social environments."[16]

In his examination of the question of whether Christianity fosters violence, Miroslav Volf has identified four main arguments that it does: that religion by its nature is violent, which occurs when people try to act as "soldiers of God"; that monotheism entails violence, because a claim of universal truth divides people into "us versus them"; that creation, as in the Book of Genesis, is an act of violence; and that the intervention of a "new creation", as in the Second Coming, generates violence.[1] Writing about the latter, Volf says: "Beginning at least with Constantine's conversion, the followers of the Crucified have perpetrated gruesome acts of violence under the sign of the cross. Over the centuries, the seasons of Lent and Holy Week were, for the Jews, times of fear and trepidation; Christians have perpetrated some of the worst pogroms as they remembered the crucifixion of Christ, for which they blamed the Jews. Muslims also associate the cross with violence; crusaders' rampages were undertaken under the sign of the cross."[17] In each case, Volf concluded that the Christian faith was misused in justifying violence. Volf argues that "thin" readings of Christianity might be used mischievously to support the use of violence. He counters, however, by asserting that "thick" readings of Christianity's core elements will not sanction human violence and would, in fact, resist it.[1]

Volf asserts that Christian churches suffer from a "confusion of loyalties". He asserts that "rather than the character of the Christian faith itself, a better explanation of why Christian churches are either impotent in the face of violent conflicts or actively participate in them derives from the proclivities of its adherents which are at odds with the character of the Christian faith." Volf observes that "(although) explicitly giving ultimate allegiance to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, many Christians in fact seem to have an overriding commitment to their respective cultures and ethnic groups."[18]

John Teehan takes a position that integrates the two opposing sides of this debate. He describes the traditional response in defense of religion as "draw(ing) a distinction between the religion and what is done in the name of that religion or its faithful." Teehan argues that "this approach to religious violence may be understandable but it is ultimately untenable and prevents us from gaining any useful insight into either religion or religious violence." He takes the position that "violence done in the name of religion is not a perversion of religious belief... but flows naturally from the moral logic inherent in many religious systems, particularly monotheistic religions..." However, Teehan acknowledges that "religions are also powerful sources of morality." He asserts that "religious morality and religious violence both spring from the same source, and this is the evolutionary psychology underlying religious ethics."[19]

Dostoyevsky rejects this linkage. He says, "We have taken up the sword of Caesar, and in taking it, of course, have rejected Thee and followed him [the devil]."[20]

Christian scriptures

Main article: Bible and violence

From its earliest days, Christianity has been challenged to reconcile the scriptures known as the "Old Testament" with the scriptures known as the "New Testament". Ra'anan S. Boustan asserts that "(v)iolence can be found throughout the pages of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the New Testament."[21] Philip Jenkins describes the Bible as overflowing with "texts of terror".[22]

In response to these charges of violence in their scriptures, many Christian theologians and apologists respond that the "God of the Old Testament" is a violent God whereas the "God of the New Testament" is a peaceful and loving God. Gibson and Matthews characterize this view as a "millenia-old bias", one that "places the origins of Judeo-Christian violence squarely within Judaism".[23]

Terence Freitheim describes the Old Testament as a "book filled with ...the violence of God". He asserts that while the New Testament does not have the same reputation, it too is "filled with violent words and deeds, and Jesus and the God of the New Testament are complicit in this violence.[8] Gibson and Matthews have a similar perspective.[23]

Gibson and Matthews make a similar charge, asserting that many studies of violence in the Bible focus on violence in the Old Testament while ignoring or giving little attention to the New Testament. They find even more troubling "those studies that lift up the New Testament as somehow containing the antidote for Old Testament violence."[24]

This apparent contradiction in the sacred scriptures between a "God of vengeance" and a "God of love" are the basis of a tension between the irenic and eristic tendencies of Christianity that has continued to the present day.

This approach is challenged by those who point out that there are also passages in the New Testament that tolerate, condone and even encourage the use of violence. John Hemer asserts that the two primary approaches that Christian teaching uses to deal with "the problem of violence in the Old Testament" are:

- Concentrate more on the many passages where God is depicted as loving – much of Isaiah, Hosea, Micah, Deuteronomy.

- Explain how the idea of God as a violent punishing war monger is all part of the historical and cultural conditioning of the author and that we can ignore it in good faith, especially in the light of the New Testament.

In opposition to these two approaches, Hemer argues that to ignore or explain away the violence found in the Old Testament is a mistake. He asserts that "Violence is not peripheral to the Bible it is central, in many ways it is the issue, because of course it is the human problem." He concludes by saying that "The Bible is in fact the story of the slow, painstaking and sometimes faltering escape from the idea of a God who is violent to a God who is love and has absolutely nothing to do with violence."[25] Ronald Clements expresses a similar view, writing that "to dismiss the biblical language concerning the divine wrath as inappropriate, or even offensive, to the modern religious mind achieves nothing at all by way of resolving the tensions in the reality of human history and human experience.[26]

The image of a violent God in Hebrew scriptures that condoned and even ordered violence posed a problem for some early Christians who saw this as a direct contradiction to the God of peace and love attested to in the New Testament. Perhaps the most famous example was Marcion who dropped the Hebrew scriptures from his version of the Bible because he found in them a violent God. Marcion saw the God of the Old Testament, the Demiurge and creator of the material universe, as a jealous tribal deity of the Jews, whose law represented legalisticreciprocal justice and who punishes mankind for its sins by suffering and death. Marcion wrote that the God of the Old Testament was an "uncultured, jealous, wild, belligerent, angry and violent God, who has nothing in common with the God of the New Testament..." For Marcion, the God about whom Jesus was an altogether different being, a universal God of compassion and love, who looks upon humanity with benevolence and mercy. Marcion argued that Christianity should be solely based on Christian Love. He went so far as to say that Jesus’ mission was to overthrow Demiurge -- the fickle, cruel, despotic God of the Old Testament—and replace Him with the Supreme God of Love whom Jesus came to reveal.[27]

Marcion's teaching was repudiated by Tertullian in five treatises titled "Against Marcion" and Marcion was ultimately excommunicated by the Church of Rome.[28]

The difficulty posed by the apparent contradiction between the God of the Old Testament and the God of the New Testament continues to perplex pacifist Christians to this day. Eric Seibert asserts that, "(f)or many Christians, involvement in warfare and killing in the pages of the Old Testament is incontrovertible evidence that such activities have God's blessing. ... Attitudes like this are terribly troubling to religious pacifists and demonstrate the kind of problems these texts create for them."[29] Some modern-day pacifists such as Charles Ravenhave argued that the Church should repudiate the Old Testament as an unchristian book, thus echoing the approach taken by Marcion in the 2nd century.[30]

Old Testament

The principle of "an eye for an eye" is often referred to using the Latin phrase lex talionis, the law of talion. The meaning of the principle Eye for an Eye is that a person who has injured another person returns the offending action to the originator in compensation. The exact Latin (lex talionis) to English translation of this phrase is actually "The law of retaliation." At the root of this principle is that one of the purposes of the law is to provide equitable retribution for an offended party.

Dr Ian Guthridge cited many instances of genocide in the Old Testament:[31]:319-320

| “ | the Bible also contains the horrific account of what can only be described as a "biblical holocaust". For, in order to keep the chosen people apart from and unaffected by the alien beliefs and practices of indigenous or neighbouring peoples, when God commanded his chosen people to conquer the Promised Land, he placed city after city 'under the ban" -which meant that every man, woman and child was to be slaughtered at the point of the sword. | ” |

The extent of extermination is described in the scriptural passage Deut 20:16-18 which orders the Israelites to "not leave alive anything that breathes… completely destroy them …".[32]thus leading many scholars to characterize the exterminations as genocide.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42] Niels Peter Lemche asserts that European colonialism in the 19th century was ideologically based on the Old Testament narratives of conquest and extermination.[43] Arthur Grenke claims that the view or war expressed in Deuteronomy contributed to the destruction of Native Americans and to the destruction of European Jewry.[44]

[New Testament

Christian interpretation of the lex talionis has been heavily influenced by the quotation from Leviticus (19:18 above) in Jesus of Nazareth's Sermon on the Mount. In the Expounding of the Law (part of the Sermon on the Mount), Jesus urges his followers to turn the other cheek when confronted by violence:

This saying of Jesus is frequently interpreted as criticism of the Old Testament teaching, and often taken as implying that "an eye for an eye" encourages excessive vengeance rather than an attempt to limit it. It was one of the points of 'fulfilment or destruction' of the Hebrew law which the Church father St. Augustine already discussed in his Contra Faustum, Book XIX.[45]

Christian teaching

Theologian Robert McAfee Brown identifies a succession of three basic attitudes towards violence and war during the history of Christian thought. The first of these attitudes was the strict pacifism of the earliest Christians; by the 3rd century, this pacifism had evolved to incorporate the concept of a just war which then led to the development of the holy war orcrusade.[46]

Pacifism in early Christianity

Many scholars assert that Early Christianity (prior to 313 AD) was a pacifist religion and that, only after it had become the state religion of the Roman Empire, did Christianity begin to rationalize, institutionalize and endorse violence to further the interests of the state and the church. Some scholars believe that "the accession of Constantine terminated the pacifist period in church history."[47] According to Rene Girard, "Beginning with Constantine, Christianity triumphed at the level of the state and soon began to cloak with its authority persecutions similar to those in which the early Christians were victims."[48] And in Ulrich Luz's formulation; "After Constantine, the Christians too had a responsibility for war and peace. Already Celsus asked bitterly whether Christians, by aloofness from society, wanted to increase the political power of wild and lawless barbarians. His question constituted a new actuality; from now on, Christians and churches had to choose between the testimony of the gospel, which included renunciation of violence, and responsible participation in political power, which was understood as an act of love toward the world." Augustine's Epistle to Marcellinus (Ep 138) is the most influential example of the "new type of interpretation."[49]

In response to the accusations of Richard Dawkins, Alister McGrath suggests that, far from endorsing "out-group hostility", Jesus commanded an ethic of "out-group affirmation". McGrath agrees that it is necessary to critique religion, but says that it possesses internal means of reform and renewal, and argues that, while Christians may certainly be accused of failing to live up to Jesus' standard of acceptance, Christian ethics reject violence.[50]

In the first few centuries of Christianity, many Christians refused to engage in military combat. In fact, there were a number of famous examples of soldiers who became Christians and refused to engage in combat afterward. They were subsequently executed for their refusal to fight.[51] The commitment to pacifism and rejection of military service is attributed by Allman and Allman to two principles: "(1) the use of force (violence) was seen as antithetical to Jesus' teachings and service in the Roman military required worship of the emperor as a god which was a form of idolatry."[52]

Origen asserted: "Christians could never slay their enemies. For the more that kings, rulers, and peoples have persecuted them everywhere, the more Christians have increased in number and grown in strength."[53] Clement of Alexandria wrote: "Above all, Christians are not allowed to correct with violence."[54] Tertullian argued forcefully against all forms of violence, considering abortion, warfare and even judicial death penalties to be forms of murder.[55][56] These positions of these three Church Fathers are maintained today by Catholics[57] and Orthodox Christians.[58]

Non-violence as a Christian doctrine

Main articles: Christian pacifism and Peace churches

There is a long tradition of opposition to violence in Christianity.[59] Some early figures in Christian thought explicitly disavowed violence. Origen wrote: "Christians could never slay their enemies. For the more that kings, rulers, and peoples have persecuted them everywhere, the more Christians have increased in number and grown in strength."[53] Clement of Alexandria wrote: "Above all, Christians are not allowed to correct with violence."[54] Several present-day Christian churches and communities were established specifically with nonviolence, including conscientious objection to military service, as foundations of their beliefs.[60] In the 20th century, Martin Luther King, Jr. adapted the nonviolent ideas of Gandhi to a Baptist theology and politics.[61] In the 21st century, Christian feminist thinkers have drawn attention to opposing violence against women.[62]

Some theologians, however, reject the pacifist interpretation of Christian dogma. W.E. Addis et al. have written: "There have been sects, notably the Quakers, which have denied altogether the lawfulness of war, partly because they believe it to be prohibited by Christ (Mt. v. 39, etc), partly on humanitarian grounds. On the Scriptural ground they are easily refuted; the case of the soldiers instructed by in their duties by St. John the Baptist, and that of the military men whom Christ and His Apostles loved and familiarly conversed with (Lk 3:14, Acts 10, Mt 8:5), without a word to imply that their calling was unlawful, sufficiently prove the point."[63]

Just war theory

Main article: Just war theory

Just War Theory' (or Bellum iustum) is a doctrine of military ethics of Roman philosophical and Catholic origin[64][65] studied by moral theologians, ethicists and international policy makers which holds that a conflict can and ought to meet the criteria of philosophical, religious or political justice, provided it follows certain conditions.

Just War theorists combine both a moral abhorrence towards war with a readiness to accept that war may sometimes be necessary. The criteria of the just war tradition act as an aid to determining whether resorting to arms is morally permissible. Just War theories are attempts "to distinguish between justifiable and unjustifiable uses of organized armed forces"; they attempt "to conceive of how the use of arms might be restrained, made more humane, and ultimately directed towards the aim of establishing lasting peace and justice."[66]

The Just War tradition addresses the morality of the use of force in two parts: when it is right to resort to armed force (the concern of jus ad bellum) and what is acceptable in using such force (the concern of jus in bello).[67] In more recent years, a third category — jus post bellum — has been added, which governs the justice of war termination and peace agreements, as well as the prosecution of war criminals.

The concept of justification for war under certain conditions goes back at least to Cicero.[68] However its importance is connected to Christian medieval theory beginning from Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas.[69] According to Jared Diamond, Saint Augustine played a critical role in delineating Christian thinking about what constitutes a just war, and about how to reconcile Christian teachings of peace with the need for war in certain situations.[70]

Jonathan Riley Smith writes,

The consensus among Christians on the use of violence has changed radically since the crusades were fought. The just war theory prevailing for most of the last two centuries — that violence is an evil which can in certain situations be condoned as the lesser of evils — is relatively young. Although it has inherited some elements (the criteria of legitimate authority, just cause, right intention) from the older war theory that first evolved around a.d. 400, it has rejected two premises that underpinned all medieval just wars, including crusades: first, that violence could be employed on behalf of Christ's intentions for mankind and could even be directly authorized by him; and second, that it was a morally neutral force which drew whatever ethical coloring it had from the intentions of the perpetrators.[71]

Holy war

In 1095, at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II declared that some wars could be deemed as not only a bellum iustum ("just war"), but could, in certain cases, rise to the level of a bellum sacrum(holy war).[72] Jill Claster characterizes this as a "remarkable transformation in the ideology of war", shifting the justification of war from being not only "just" but "spiritually beneficial.[73] Thomas Murphy examined the Christian concept of Holy War, asking "how a culture formally dedicated to fulfilling the injunction to 'love thy neighbor as thyself' could move to a point where it sanctioned the use of violence against the alien both outside and inside society". The religious sanctioning of the concept of "holy war" was a turning point in Christian attitudes towards violence; "Pope Gregory VII made the Holy War possible by drastically altering the attitude of the church towards war... Hitherto a knight could obtain remission of sins only by giving up arms, but Urban invited him to gain forgiveness 'in and through the exercise of his martial skills'". A Holy War was defined by the Roman Catholic Church as "war that is not only just, but justifying; that is, a war that confers positive spiritual merit on those who fight in it".[74][75]

In the 12th century, Bernard of Clairvaux wrote: "'The knight of Christ may strike with confidence and die yet more confidently; for he serves Christ when he strikes, and saves himself when he falls.... When he inflicts death, it is to Christ's profit, and when he suffers death, it is his own gain."[76]

According to Daniel Chirot, the Biblical account of Joshua and the Battle of Jericho was used to justify the genocide of Catholics during theCromwellian conquest of Ireland.[77]:3 Chirot also interprets 1 Samuel 15:1-3 as "the sentiment, so clearly expressed, that because a historical wrong was committed, justice demands genocidal retribution."[77]:7-8

No comments:

Post a Comment

please make the cooments and share